[Content Warning: this review addresses suicide and self-harm]

“I have decided to keep a journal.”

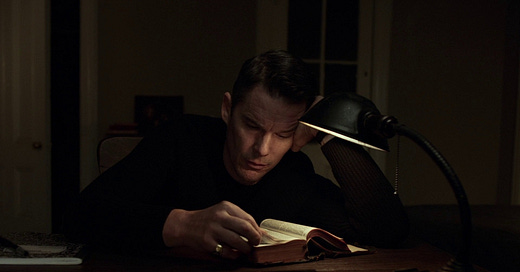

First Reformed (2017, dir. Paul Schrader) forces patience on its audience. From the film’s opening shot—a slow crawl up to the old white building known as First Reformed Church—to its opening monologue, in which Reverend Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke) endeavors to track his foreboding thoughts, First Reformed teaches viewers to contemplate, with unrelenting scrutiny, their own lives and the world around them.

Especially haunting is the film’s assessment of prayer.

Reverend Toller is no stranger to prayer—in fact, he may be the only one in his miniscule community that truly knows how to pray: “How easily they talk about prayer, those who have never really prayed.” For Toller, prayer is war. It’s as brutally honest and self-abating as his journal experiment—or perhaps even more so, considering the idea that prayer is communication with God Himself. Nevertheless, the Reverend pulls no punches in his prayer and journal life. On the latter, he writes, “When writing about oneself, one should show no mercy.” As the film progresses, Rev. Toller is less concerned with showing himself no mercy, and more concerned with punishing himself for his own sinfulness.

While wrestling with (what he later learns is) cancer, Rev. Toller meets with Mary (Amanda Seyfried) and Michael Mensana (Philip Ettinger) about Michael’s climate change activism and his reservations about bringing a baby into the world he sees is in constant decay. Their conversation is deep and prescient. Both Michael, the skeptic, and Toller, the Reverend, reveal their doubts and limited knowledge of God and the future. “Can God forgive us for what we’ve done to this world?” Michael asks. “I don’t know,” Toller admits, “Who can know the mind of God? But we can choose a righteous life. Belief. Forgiveness. Grace covers us all. I believe that.” Michael’s questionable plans to commit suicide by use of a bomb vest are thwarted by Rev. Toller and Mary, but he still manages with a shotgun—crumbling, tragically, under the weight of hopelessness and helplessness.

Reverend Toller struggles to preach to an almost-empty church every Sunday; he struggles to say with confidence what sins are forgivable and which ones will reap damnation; his only confidence is some morbid twist on John the Baptizer’s refrain: “He must increase, but I must decrease” (John 3:30). As Rev. Toller’s health—both mentally and physically—decreases, and his church is not-so-subtly becoming a tourist attraction, he commits self-sabotage. If it weren’t so morbid and destructive, it might pass for humility.

In step with other A24 films, such as The Witch (2015, dir. Robert Eggers), It Comes at Night (2017, dir. Trey Edward Shults), and A Ghost Story (2017, dir. David Lowery) First Reformed is a low-profile, low-production film. Shot in 1.33:1 (or 4:3) aspect ratio, the film prioritizes straight-on character shots (mainly of Ethan Hawke) and prizes symmetrical alignment (such as Rev. Toller’s car in front of Mary and Michael’s house). These choices make the film slightly more claustrophobic—as if the viewer is forced, not to see pseudo-piety at a distance, but to confront it face-to-face. The cinematography is equally stunning and eerie. The film’s visual editing settles on muted colors; like the dead of winter, even the sun’s light seems gray.

I am convinced that religious persons who undergo the longsuffering of watching First Reformed experience it on another, deeper level than their non-religious counterparts. As a Christian, I could not help but respond to Rev. Toller’s self-loathing with compassion; I was ready to give a Scripture or a prayer that would help him find comfort in his ailment. When Toller and Michael were discussing God and climate change, I had answers at the ready. And when Toller was outraged at Abundant Life Ministries’ attempts to make First Reformed Church an attraction, rather than a sanctuary, I too was enraged. Such problems are all too pervasive in Christian life.

An intriguing trend in film and TV is to portray the religious person as an abuser, a fraud, or the most vile person in the story. A recent example is in The Last of Us (2023–), but the trope goes back decades; an older example is Carrie (1976, dir. Brian de Palma). In First Reformed, however, we pity Rev. Toller. Why? I think part of the equation is that his abuse, harm, and hypocrisy are all self-oriented. The most poignant example, which harkens in us not anger, but compassion, is in the film’s final scenes.

As First Reformed Church’s 250th Anniversary re-consecration service begins, Rev. Toller straps Michael’s bomb vest to his chest, under priestly robes. Then—he sees Mary. He told her not to come! But here she is, walking in, finding a seat at the church she grew up going to.

Gnashing his teeth, he throws the vest off; he grabs razor-wire, slowly and achingly wrapping it around his uncovered torso. His drinking problem will soon come to an end; he dumps out the remaining whiskey in his rocks glass, only to replace it with a double of drain cleaner. What was going to be an act of self-harm and violence against hundreds became so solitary and self-abating that it would only end in his demise. That’s the premise of the film. It’s why, though the religious person in the film is committing equally as harmful and abusive acts, we don’t get mad or denounce Christianity—we mourn.

The Reverend’s earlier claim acts as the film’s thesis:

“Reason provides no answer. […] Wisdom is holding two contradictory truths in our mind, simultaneously: hope and despair. A life without despair is a life without hope. Holding these two ideas in our head is life itself.”

Thus, when Rev. Toller dons the bomb vest under his priestly robes, the film’s arc is complete. Hold these in tension: life and death; hope and despair; ultimate good and ultimate evil; peace and violence.

But one person stands in the way of even his own self-destruction. As he lifts the cup of wrath, he turns to see Mary, his Savior-figure. He drops the glass. He runs to her, kissing and embracing her. (I could not help but think that the razor-wire was ever driving into his skin as he hugged her tightly.) The film abruptly ends.

For these reasons, First Reformed has provided viewers with a most unconventional and challenging depiction of religiosity.

Essentially, First Reformed depicts the Church as everything except what it should truly be. For Abundant Life Ministries, the building is a money-grab; for Rev. Toller, it’s a prison cell; for parishioners, it’s a drab Sunday held together by no more than a hollow sermon and a broken organ. First Reformed Church, like its leader, is a shell of what it could be.

With First Reformed as a skeleton of past potential, the film’s starting-point elicits a level of concerned empathy. Anyone with a remote notion of the religious life—that it calls for peace, life, love, goodness, and truth—or even the desire for human flourishing is burdened by its absence in First Reformed.

But therein lies beauty.

The haunting realities of First Reformed feel more personal and relatable than a religious man whose life is all together. The film’s end—a man finding “salvation” from himself in a kind, pure woman—is triumphant and also intriguing. Paul Schrader is no stranger to bold depictions of Christianity (e.g., The Last Temptation of Christ [1988, dir. Martin Scorsese]). He brings his own childhood experience in the Reformed Church to life, which explains why Rev. Toller finds salvation in a woman, even as he stands inside a church and under the eye of God.

But the film ends there. Halfway through kissing and dancing in the green room, while Esther (Victoria Hill) sings a hymn in the sanctuary, the screen goes dark. Inasmuch tension as there is between hope and despair, so there is between the state of Rev. Toller. Has he found salvation in something beyond God? Does he consider Mary (perhaps ironically) his highest gift from God? Does the journal experiment continue? Will he remain the Reverend of First Reformed Church? Will he become a climate change activist?

As with the film’s opening, we’re left with a confusing sense of melancholy and religiosity—with patience, we contemplate the darkness, perhaps our inner darkness; with wisdom, we hold in tension despair over the film’s first two hours and hope from its last moments.

“Courage is the solution to despair.”